When the Meiji government transferred Japan’s capital to Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka were drastically damaged: as a matter of fact, their population drastically declined.

However, with establishment of the Arsenal Armory, Sakai Spinning Factory, Osaka Stock Exchange, and the foundation of the Osaka Spinning Company which had global-scale production capacity at the time, Osaka gradually got in orbit as an industrial city. Accordingly, the drastic improvement of Yodo River along with the assurance of water sources became urgent issues.

Meanwhile, Kyoto was also planning a miraclous project which was to have a decisive impact on Yodo River in the future.

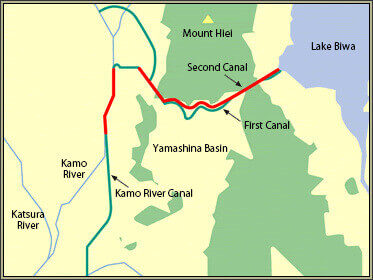

The project was the Lake Biwa Canal (1890). The concept itself emerged years earlier, which involved digging a tunnel through Mount Hiei in order to draw abundant water of Lake Biwa to Kyoto.

Some of its main objectives were irrigation, water transport, dyeing and weaving and tap water. What made the project truly revolutionary in terms of usage of Yodo River, or for domestic industries in the following years, was the world’s first attempt to introduce hydroelectric power generation. This power plant would later supply electricity for Kyoto to operate the first electric trains in Japan.

Lake Biwa Canal

Although in later years, integrated river projects which are namely multi-purpose came to normally include power generation, irrigation, flood control, water service, regulations of river flow etc., this Lake Biwa Canal should be the first multi-purpose development project in Japan. Particularly, the Lake Biwa Canal Project brought the strong impact on the other hydroelectric power generation in Japan.

Large-scale power plants such as the Uji River Power Plant (1913), Shizu River Power Plant (1924), and Oomine Power Plant (1927) were subsequently constructed along the Yodo River system. Osaka would take the lead of Japan’s industrial revolution as the city of heavy and chemical industries. In this way, the improvement of Yodo River shifted from sabo (erosion and the torrent control) and water controlling dikes to the construction of artificial rivers that fortified embankments to secure irrigation and flood control.

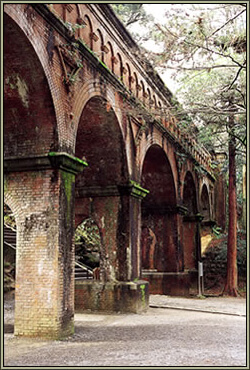

Suirokaku Aqueduct in Nanzenji Temple

(Aqueduct on Lake Biwa Canal)

In 1896, along with enactment of the River Act, a national construction project was launched to improve Yodo River.

Let’s take a look at how these groups of banks and weirs have affected agriculture in the area.

In the Kawachi Plain, there is a city called Shijou-nawate. The word nawate originally means “paddy road,” but in this area, the term specifically referred to a “small encircling levee.” Each village would surround its fields with temporary levees to guard them from floods.

To make a long story short, the lower part of Yodo River was a polder area.

Within these areas, a unique irrigation practice known as koshikoku used to be practiced. This involved paying a fixed amount of rice to downstream villages each year as compensation for land destroyed due to drainage from upstream villages that ran through downstream villages. Usually, in any village, upstream inhabitants have more power than their downstream counterparts. Such a practice indicates that this case is contradictory to the usual case and how significant a problem akusui (drainage from rice paddies, literally meaning “bad water” in Japanese) was in the area.

The stronger Yodo River’s embankments became, the more difficult it became for nearby communities to irrigate and drain their fields. As the entire nation proceeded toward modern industrialization, farmers had no choice but to take up the difficult challenge of rearranging traditional water-use systems by their own hands.

For example, the Shin-An Land Improvement District, which still holds great leadership over the right bank of Yodo River, was at the time comprised of associations of 64 towns and villages, and the fierceness of their battles stands out in Japanese agricultural history to such an extent that these conflicts have been taken as the subject of academic papers.

However, modernization of Yodo River did not necessarily bring only disadvantages.

Floods and inundation damage dramatically decreased, leading to the promotion of drainage improvement projects downstream. As industrialization in Osaka advanced, water pumps, engines, and chemical fertilizers were produced and sold at comparatively low prices, greatly to promote the modernization of farm villages.

The land reclamation in Oguraike, pioneering Japan’s national reclamation projects, deserves special mention.

In year 1906, rerouting of Uji River completely cut off this pond from Uji River, resulting in the lowering of water level. While facing many obstacles, due to fervent movements of local inhabitants, the project was launched as Japan’s first national land reclamation project in 1933 (completed in 1941).

Reclaimed Land of Oguraike

634 hectares of farmland was reclaimed, along with improvement of 1,260 hectares of surrounding farmland. In the days when the increase of food production during and right after World War II, this region alone made an enormous contribution to the nation, including a marvelous harvest of 30 thousand koku (roughly 5.4 million liters: 1 koku being approximately 180 liters).

Land reclamation is often confused with landfill, but these two are different.

This area is still located in the lowest part of the Yamashiro Basin.

Machines forcibly drain a huge quantity of water at a rate of 42m3 per second.

While urbanization progresses in the surrounding area, this region produces not only rice but also local varieties of vegetables of Kyoto, such as the famous Shogoin Globe radish.

This area still remains to this day a great agricultural area which is symbolic of the Kidai region.