“History” in a narrow sense, naturally comes out in places where water is available. It is no exaggeration to say that the history of Azumino is synonymous with the history of water and land.

Rice paddy communities can subsist with the condition that people can draw enormous amounts of water from rivers.

Usually, rivers run through the lowest parts of an area, so much so that people need to get water from far upstream or at least from a higher elevation than their village in order to secure a certain gradient of a waterway.

If one wanted to prevent fields from drying up during long drought spells, the first thing that would come to mind was construction of large canals from rivers. However, those canals would also bring too much floodwater during heavy rainfall.

We can only imagine how difficult it was to create a canal that neither dried up nor flooded in a region where rivers disappeared into underground in natural conditions.

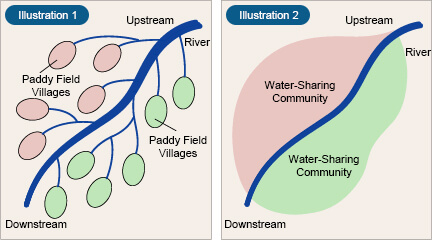

People built an irrigation canal from a river, and subsequently a small village was formed. If the river still carried extra water, afterward another village would build its own canal. And more and more villages would take in water.

In this way, many villages would be built along one river to share the available water (see Illustration 1).

But river flow is not constant. Especially during dry season in summer, if upstream villages took in too much, downstream villages could not survive.

Further, conflicts between the right and left banks were also bloody affairs.

Thus, water-sharing communities, comprising several localities depending their subsistence on one river, formed over many years of repeated conflicts and reconciliation (see Illustration 2).

Reprinted from Inochi No Mizu (Water of Life) by the Nagano Prefecture Toyoshina City Board of Education

Original villages, unlike today’s housing complexes or newly developed towns, were so settled that they would painstakingly share meager flow of the river as if unraveling a piece of twine, and at times stole water from each other: thus, people spent astounding amounts of time, labor, and conflicts forming their villages much like an old tree carving its history of struggles against the nature on the growth rings of the trunk.

Reprinted from History of Land Improvement in Nagano Prefecture, Volume 2

The responsibility for adjusting and managing water use of those villages, which was the most difficult task, have been shouldered by the Land Improvement Districts, as are known today. They have essentially been playing the same role as the core of each village for more than 1,000 years.

The map on the left shows the main irrigation canals of this area. The canals are like blood vessels in the human body, or arteries. For example, if we zoom in the rectangular zone on the map, we can see that, as shown in Illustration 3, there are even smaller canals spreading out like capillaries or peripheral nerves, each carrying water to every part of Azumino, leaving no area non-irrigated.

These are current canal maps, which are basically little different from maps drawn in the Edo era (17th to 19th centuries) or earlier.

The average length of main irrigation canals bringing water to one hectare or more of farmland in this region is 124 meters (approximately 1.2 times longer than the average for all of Nagano Prefecture). The average of Japan is 76 meters, or nearly half.

This means that the concentration of irrigation canals in Azumino is twice as dense as the other parts of Japan.

There are actually very few records about these water distribution systems. However, we can say that these figures speak eloquently about the hardships shouldered by the tens of thousands of farmers who lived and died in this land.