We have seen how the sweat and blood of millions of farmers dramatically transformed Azumino from a barren land to fertile plain. However, the summer droughts, which have affected people through the ages, are still obvious in this region today.

Farmers need water for life. By balancing water resources among water users the lives of the entire villages were secured.

It is said that downstream villagers would negotiate with upstream dwellers throughout the summer at times offering sake, money and gifts in return for favors.

Water rights were especially complicated along Azusa River.

This zone had old irrigation canals dating back to the Heian era (8th C) . Besides, water gates located in the upper streams of the opposite bank belonged to different clans. So the disputes involved villages both upstream and downstream, on the right riverbanks and the left, being trailed with complicated feuds from the Edo era.

Bloody conflict in 1924

In this summer this area was attacked by an exceptionally long drought. Roughly 1,500 hectares of paddy fields in the Azusa alluvial fan had almost no harvest. Farmers despaired. Facing each other across the river, they stood on banks with sticks and sickles in hand, threw stones at each other, exchanged blows. Ultimately, large police units were dispatched. This became a turning point, and finally a prefectural irrigation project was launched in 1926 that would merge the water intakes at the seven left-bank weirs and the seven right-bank weirs into one. Plans were drafted for construction of main irrigation canals as well as land consolidation.

The tragic history of the region over a thousand years finally ceased.

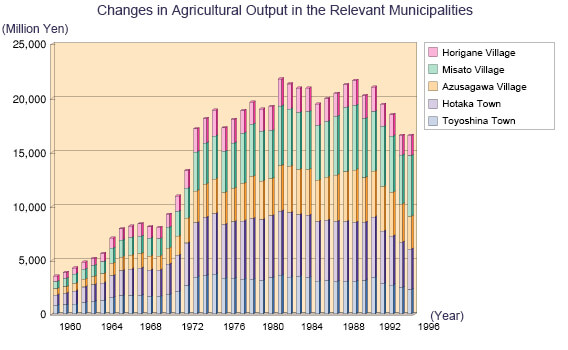

A national project was launched in 1950 where the Azusa headworks, irrigation channels and other modern engineering facilities were constructed: subsequently, the development of agricultural villages moved forward steadfastly in Azumino.

Farmers did not battle only for water rights. The alluvial fan of the Kurosawa River, the aforementioned shirinashigawa (“river without downstream”’), was an expanse of forestland before, belonging to a local clan, covered with Japanese red pine. It was later designated as a national forest. Accordingly request for the sale of this government property was granted. The forest was then reclaimed, and in 12 years this land was developed to the farmland. However, this reclaimed land caused over nearly 10 years of tireless conflict that started around 1930.

It was only after 1965 that agriculture finally stabilized in Azumino, when another national irrigation project was launched. The dam for hydroelectricity was built on the upper streams of Azusa River and some of the main irrigation canals were rehabilitated. At the same time, main canal of 19-kilometers connecting to the peaks of the composite alluvial fan was also constructed. We can call it as the “largest yokozeki (horizontal channel) in Azumino” which would be achieved by modern irrigation, drainage and reclamation engineering. Thanks to this new canal, paddy fields are assured of a stable supply of irrigation water. Further, sprinklers were introduced for non-paddy farming, turning the reclaimed area along Kurosawa River into a huge apple orchard.

Shiroumadake、Jounendake、Chougatake…

Farming in Azumino, which was once carried out according to a seasonal agriculture calendar with the snow-shape of Northern Alps, has changed from the man-and-horse agriculture to the machine one. Accordingly, agriculture and rural development projects have come to include land improvement, extensive agricultural road construction, and other projects that focus not only on water-use alone, but on enhancing the efficiency of the work as well.

The old barren farmlands of Azumino have indeed been magnificently transformed.

Today, the region has one of the most unique and breathtaking rural landscapes in Japan attracting many tourists. It is hard to remember the harsh history of life-or-death battles over water or hard labor of the guardians of weirs and other facilities.

We also need to know what these changes in agriculture and agricultural communities are bringing about today.